Download PDF:

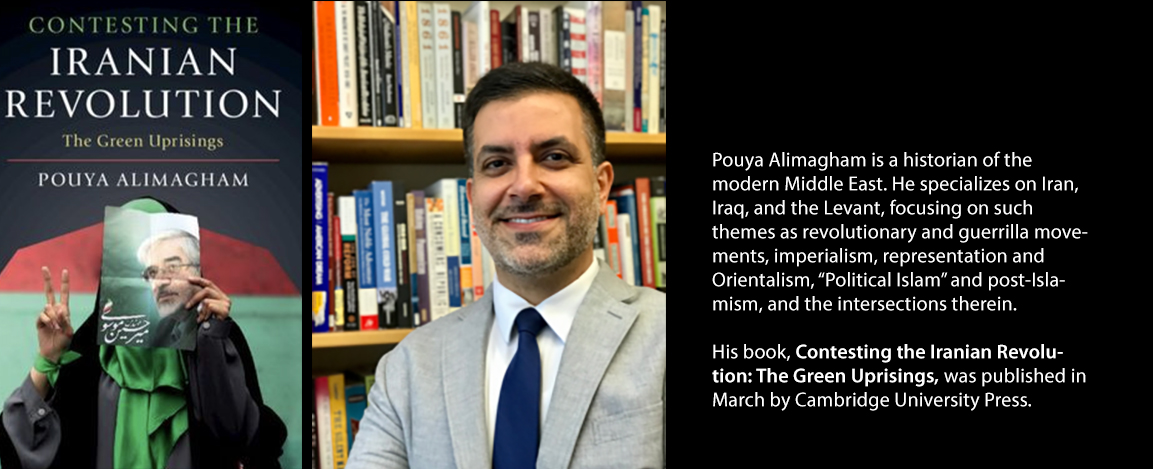

In Contesting the Iranian Revolution: The Green Uprisings, Pouya Alimagham harnesses the wider history of Iran and the Middle East to highlight how activists contested the Islamic Republic's legitimacy to its very core. Below is an excerpt from chapter one and is used by permission of the publisher Cambridge University Press.

Iran is one of a number of countries that give real-world application to the Orwellian mantra that “history is written by the victors.”1 Indeed, the militant clerics who consolidated power at the expense of all the other revolutionary factions have worked tirelessly to present their version of the Iranian Revolution’s history as the only version, best encapsulated by the state’s preferred revolutionary slogan, “Independence, Freedom, Islamic Republic” (esteqlāl, āzādī, jomhūrī-ye eslāmī). For years, the Iranian government has presented this one-sided history to the benefit of its ruling class and self-affirming ideology.

Just as the events of 1978‒1979 are far more complex and disputed than the state would like to admit, the historic uprising of 2009 is equally contentious. Years after the revolt, the Iranian government continued to refer to the Green Movement as “the sedition” ‒ a conspiracy orchestrated from abroad and without organic roots within the country.2 Inspired by studies that have contested the official narrative of the Iranian Revolution, this work aspires to do the same with the official narrative of the uprising in 2009.

Iran’s protracted post-election uprising, the Green Movement, erupted more than two years before the protest movement in Tunisia ignited the firestorm of revolution that became known as the Arab Spring (“Arab Uprisings”).3 Iran’s revolt was hailed as the largest and most formidable challenge to the Iranian state since the seismic events of 1978‒1979 that shaped the way regional leaders, military officers, foreign heads of state, journalists, analysts and commentators, and, most significantly, various peoples view Iran and the Middle East. The Iranian Revolution of thirty years before, perhaps more than any other revolution of the twentieth century, created a “shock-wave” with ramifications that were “felt round the world”4 and which continue to reverberate throughout the country and the region.

In 2011, observers and politicians viewed Egypt, an Arab country that has not had formal relations with Iran since the Iranian Revolution, through the prism of the very revolution that precipitated the severance of ties between the two. As popular forces engulfed Egypt in revolt against Hosni Mubarak, the country’s “Arab president for life,”5 American and Israeli leaders invoked the specter of Egypt becoming the “next Iran.” Israeli Premier Benyamin Netanyahu stated, “Our real fear is of a situation that could develop… and which has already developed in several countries, including Iran itself: repressive regimes of radical Islam.”6 In an open letter to President Obama, American Senator Mark Kirk called for direct US intervention in the affairs of Egypt to support the “secular nationalists” and take action to “defeat” the Muslim Brotherhood so the organization did not “follow Iran’s revolution, turning Egypt into a state-sponsor of terror.”7 In the aftermath of Mubarak’s ousting, the ruling Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF) declared that “Egypt will not be governed by another Khomeini.”8 Even Ayatollah ʿAli Khamenei, Iran’s Supreme Leader, referenced Iran’s 1978‒1979 revolution, claiming that it served as an exemplar for action for fellow Muslims in the era of the Arab Uprisings.

Today’s events in North Africa, Egypt, Tunisia, and several others, have a different meaning for the Iranian nation. They have a special meaning. These events are part of the Islamic Awakening, which can be said is itself a result of the victory of the great Islamic Revolution of the Iranian nation.9

Some similarities such as strikes were key to both the Iranian Revolution and the Arab revolts in Tunisia and Egypt. Despite the fact that no strikes occurred during the heyday of the Green Movement, the Arab Spring had more in common with the Iranian activists of 2009 in terms of their goals, youth demographic, and use of modern technologies, than with the Khomeini-led revolution and its outcome, but such commonalities either made for politically inconvenient comparisons at best or Orientalist generalizations at worst.

According to Kirk, Netanyahu, the SCAF, and Khamenei, it was of no consequence that the Iranian Revolution and the uprising in Egypt were separated by more than three decades with an abundance of differences. Such a generalization and simplification minimizes the social, demographic, political, cultural, geographical, and historical factors that distinguish these two countries and their historical trajectories. The leaps of history overlooked many significant differences: economic factors, the fundamental differences between Iranian Shiʿism and Egyptian Sunnism, the role of ideology, the subtle but important distinctions in these countries’ Islamist movements, and the degree of autonomy of each countries’ religious institutions vis-à-vis the state. Furthermore, the Cold War context crucial to Iran in 1979 and the contemporary political nuances relevant to Egypt, and the geographical realities between Iran bordering the Soviet Union in 1978 and Egypt bordering Israel and a Hamas-ruled Gaza Strip in 2011 are all disregarded to draw problematic parallels.10 Moreover, such a narrow perspective ignores the crucial role of the sizable Christian minority in Egypt that makes it all the more difficult for Egypt to become the “next Iran."11

Similarly, the Green Movement of 2009 could not avoid being seen through the prism of the Iranian Revolution. The actual connection between the two, however, is much more profound. Whereas in the context of the 2011 uprising in Egypt, foreign leaders either drew upon their limited knowledge of the Iranian Revolution in anxiety or invoked that history in the service of their political agendas, journalists inside Iran referenced the Iranian Revolution when reporting nearly every momentous occasion in the uprising in order to underscore its historical gravity. For instance, Al Jazeera’s opening line in its report of the second day of the uprising referred to it as “the biggest unrest since the 1979 revolution,”12 "The largest and most widespread demonstrations since the 1979 Islamic revolution…”13 For outsiders the revolt did indeed invoke the Iranian Revolution because it brought millions of Iranians to the streets in defiance of their government.

The street marches were one of the most awe-inspiring and memorable aspects of the Iranian Revolution. Millions of women and men marched, often under the threat of state violence, to register their revolutionary protest against the monarch’s absolutism. Charles Kurzman, author of The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran, notes that “It is almost unheard of for a revolution to involve as much as 1 percent of a country’s population. The French Revolution of 1789, the Russian Revolution of 1917, perhaps the Romanian Revolution of 1989—these may have passed the 1 percent mark.”14 Yet, on December 10 and 11, 1978, between six and nine million Iranians (some have estimated the number as high as 17 million15, between a third and half of the population, took part in demonstrations in what Kurzman believes could have been “the largest protest event in history.”16 So vaunted and historically consequential were these street demonstrations that post-revolutionary17 Iranian leaders advised Palestinians “to deploy the multi-million tactic to destroy the Israeli army and Israel itself.”18 The long span of three decades did not dissuade journalists from invoking the events of 1979 when the 2009 post-election uprising likewise prompted millions of Iranians to once again flood the streets against their government. As before, they voted with their feet, and under the threat of state violence, against a government that they believed did not respect the ballot box.

The uprising in 2009, however, shares a deeper history with 1978‒1979 that transcends the time and space of the momentous street demonstrations. The repertoires of action that were cemented in the official narrative of the revolution informed the actions of Green Movement activists in 2009, giving their reprogrammed methods historically infused importance and meaning.

Bibliography

1. The famous quote is tellingly attributed to Winston Churchill, the British premier who ordered his secret service to work hand in hand with the American CIA to orchestrate the overthrow of the Iranian government on August 19, 1953.

2. Fetneh-ye 88 toṭ’eh-ye doshman ʿalayh-i īrān būd.” Fars News Agency, Aug 10, 2014. www.farsnews.com/newstext.php?nn=13931007001669. Also see: “Fīrūzābādī: yowm allāh-i nohom-i dey maḥṣūl-i ensejām-i ʿomūmī-ye mardom shod.” ISNA, Jan 1, 2014. http://goo.gl/Ymi2h3. There is no doubt that the US government, especially during the second Bush administration, was spending millions of dollars to “promote democracy” in Iran. There is significant doubt, however, about the destination of the allocated US$75 million, an amount that was increased in later years. While the Iranian government suspected that the money was used to finance dissidents and groups to launch a “velvet revolution,” the bulk of the funds, according to one seasoned observer, was used for Persian language programming such as Radio Farda and Voice of America. What is certain is that the news of the fund’s establishment undermined “the kind of organizations and activists it was designed to help, with U.S. aid becoming a top issue in a broader crackdown on leading democracy advocates over the past year, according to a wide range of Iranian activists and human rights groups.” See Robin Wright, “Iran On Guard Over U.S. Funds,” The Washington Post, April 28, 2007. www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/04/27/AR2007042701668.html.

3. “Arab Spring” is a misnomer because it incorrectly implies that Arabs were apathetic and complacent until 2011. Arabs have busied themselves with violent and nonviolent uprisings throughout the modern period in the Middle East and North Africa. The Palestinian uprisings (1936‒1939, 1987‒1993, and 2000‒2005) are just three examples of the nonviolent and violent historical occurrences that predate the “Arab Spring.”

4. This phrase is a headline to a news piece in The Observer. See “Shock-wave felt round the world,” The Observer, January 7, 1979, p. 9.

5. To quote the title of Roger Owen’s The Rise and Fall of Arab Presidents for Life (Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2012).

6. Ian Black, “Egypt set for mass protest as army rules out force,” The Guardian, January 31, 2011. Accessed March 25, 2011. www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/jan/31/egyptian-army-pledges-no-force.

7. Mark Kirk, “Press Release of Senator Kirk: Senator Kirk Statement on Muslim Brotherhood.” Personal Website. February 2, 2011. Accessed March 25, 2011. http://kirk.senate.gov/record.cfm?id=330818. It is also important to note that Senator Kirk’s obsession with the Iranian government has led him to advocate policies that not only target the Iranian government but also harm the civilian population, an outlook best captured in his own callous words: “‘It’s okay to take the food out of the mouths of the Iranian people to punish their government for its misdeeds.” Eli Clifton and Ali Gharib, “Pro-Sanction Group Targets Legal Humanitarian Trade with Iran,” The Nation, November 13, 2014. Accessed May 22, 2015. www.thenation.com/blog/190601/pro-sanctions-group-targets-legal-humanitarian-trade-iran.

8. “Army says no to ‘Khomeini rule’ in Egypt,” ahramonline, April 4, 2011. Accessed April 4, 2011.http://english.ahram.org.eg/News/9321.aspx.

9. ʿAli Khamenei, “Khoṭbehhāye namāz jom’eh-ye tehrān + tarjomehye khoṭbeh-ye ʿarabī.” leader.ir, February 5, 2011. http://farsi.khamenei.ir/speech-content?id=10955.

10. For a more detailed treatment, see Pouya Alimagham, “The Iranian Legacy in the 2011 Egyptian Revolution: Military Endurance and U.S. Foreign Policy Priorities,” UCLA Historical Journal, 24(1) (2013).

11. The fact that Copts constitute 10 percent, or nearly 10 million Egyptians, means that it is far more difficult to establish an Islamic government in Egypt than in Iran, which did not have such a large religious minority in 1979.

12. “Poll results prompt Iran protests,” Al Jazeera, June 14, 2009. Accessed August 7, 2010. http://english.aljazeera.net/news/middleeast/2009/06/2009613172130303995.html.

13. Parisa Hafezi, “Thousands mourn Iranians killed in protests,” Reuters. June 19, 2009. http://in.mobile.reuters.com/article/worldNews/idINIndia-40437520090618.

14. Charles Kurzman, The Unthinkable Revolution in Iran (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004), p. 121.

15. Hamid Dabashi, Iran, the Green Movement and the USA (London & New York: Z Books, 2010), p. 207.

16. Kurzman, p. 122.

17.By “post-revolutionary,” I mean the period immediately after February 11, 1979, the date of the revolution’s victory, and not a period in which Iran has begun to move past the goals and ideals of the revolution.

18. Faleh A. Jaberi, The Shiʿite Movement in Iraq (London: Saqi Books, 2003), p. 250.