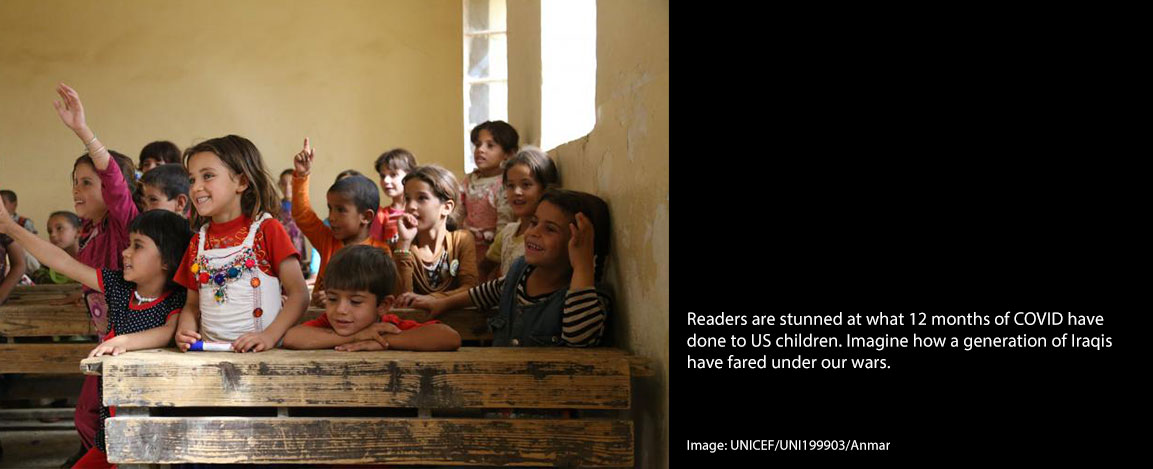

Robert E Wilhelm Fellow Steven Simon writes here in Responsible Statecraft about the impact of 30 years on war on Iraqi children.

The New York Times reported this morning that the pandemic reversed 20 years of progress in reading and math among elementary school students in the United States. Commentators emphasized the dire effect this would have on life prospects for these children and, by implication, the American economy at an especially challenging moment in its history.

These are easy to imagine. The structure of the labor market increasingly demands greater computational and literacy skills; upward financial and social mobility hinges on successful navigation of this market. And administrative states, such as the US, require these skills in the labor force for effective governance, let alone national defense. So, the impact of the pandemic on education and therefore on the nation’s future will be profound.

This awful news should help Americans better understand the effects of violent conflict and economic sanctions on countries around the world. Their populations have been battered by the equivalent of terrible pandemics every year. When we observe political instability, a shattered middle class, high poverty rates, and poor economic performance in say, Iraq, it is easy to blame these conditions on intrinsic social defects.

While cultural factors might play a role, they are difficult to define and nearly impossible to measure. Other, secular factors, especially the destruction of educational systems and psychological and nutritional effects on children who grow up to participate and shape their countries’ lives can be observed and quantified.

The Iraqi educational and public health systems have been under severe stress since the first Gulf War. Following that short sharp conflict, the UN imposed sanctions on Iraq that compounded and prolonged the effects of the war itself. Scarcity, inflation, diminished administrative capacity, bouts of renewed fighting severely damaged schooling and children’s health.

The second Gulf War and the civil war it triggered finished what the first war and twelve years of sanctions started. The proverbial lost generation is now responsible for their country’s well being. But traumatized by war and poorly educated, they are not especially well-equipped for this momentous task. Scholars have documented similar correlations between educational shortfalls due to conflict and sanctions and adverse political and economic outcomes further down the road. The Quincy Institute has documented the demolition of Syria’s educational and public health delivery systems by war and sanctions.

As we in the United States cope with the longer-term effects of a single pandemic on American children, we should think about the consequences for war torn and sanctioned societies of educational deprivation for, among other things, political stability. The costs of conflict and message sending via damage to the minds and bodies of children can be extremely high.