Its monarchy has left Saudi Arabia fragile and unbalanced.

Jamal Khashoggi and I came from very different backgrounds, and this shaped our views on the politics of our Saudi homeland. There were many issues on which we didn’t agree. But we did share one crucial belief: that untrammeled power is always a danger—and particularly in the case of Saudi Arabia.

Jamal, as he was perfectly willing to acknowledge, was born into a position of privilege. He was a product of the system and, despite his clashes with Saudi authorities over his journalism, was convinced that the politics of the royal court could be swayed by words of wisdom. He believed that the Saudi monarchy, with all its limitations, was the glue that kept Saudi Arabia together.

I do not. Unlike Jamal, my activism has rarely focused on influencing the ruling elites but rather on elevating the capacity and voices of the marginalized. My view of the royal family has always been correspondingly skeptical.

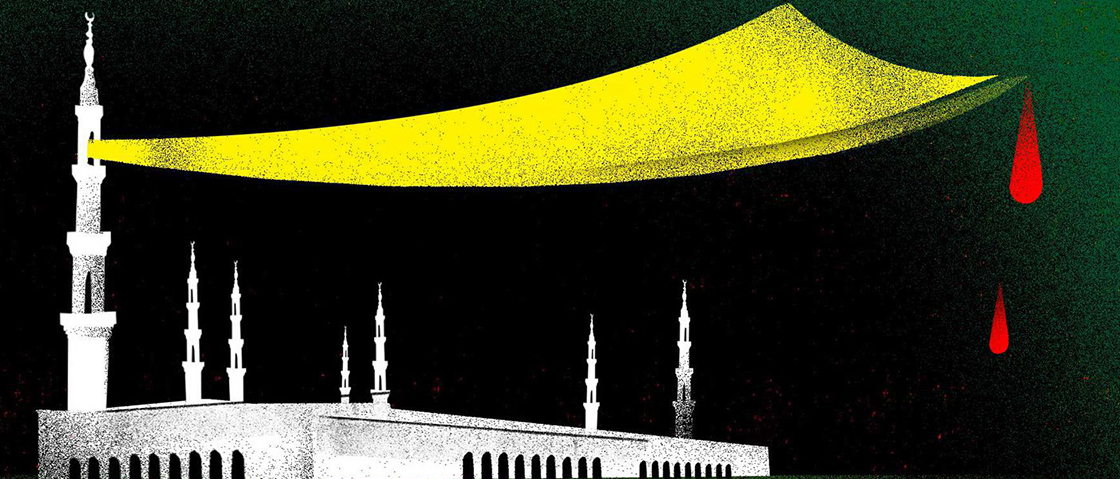

And yet, when we first met in the United States after Jamal had left Saudi Arabia in 2017, we discovered common ground. We both agreed that the lack of checks and balances in the Saudi system was a crucial problem, one aggravated by current circumstances. A country that was established as an absolute monarchy has dangerously drifted into even more of a monopoly of power with the rise of Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who has control over both resources and politics.

There is a clear pattern of human rights abuses without meaningful checks since the crown prince came to power. An early signal of this trend was nothing less than Saudi Arabia’s role in creating one of the worst man-made catastrophes in Yemen. This was followed by the government’s decision to round up of virtually every person or group with the potential to resist its abuses of power. Hundreds of journalists, thought leaders, religious reformers and women’s rights activists were viciously targeted, sending a clear message that no one in Saudi Arabia would be allowed to independently influence public discourse or raise legitimate policy concerns.

The dangers caused by the absence of balances and checks on power have naturally extended to the economy. Take the recent attack on Saudi Arabia’s Aramco oil facilities. After an attack on the country’s most valuable industry, any elected, democratically accountable national leader would focus on learning as much as possible about what happened and finding solutions to the crisis that ensued. But on the morning of the attack, Mohammed — the minister of defense and de facto ruler of Saudi Arabia—was attending a camel race rally. There is no more pathetic picture to reflect the monarchy’s self-centered disregard and the absence of ordinary citizens’ voices or engagement.

The monarchy has positioned itself at the center of statecraft in Saudi Arabia without any independent institutions. As a result, citizens have become increasingly dependent on the monarchy’s whims and decision-making — and faced further crackdowns if they tried to organize for change outside the system. In today’s Saudi Arabia, no one independent institution exists, and no one is able to safely speak truth to power. Even those like Jamal, who supported the monarchy as a system, understand the perils of this reality.

This fragile system of governance has left the fate of the country in the hands of Mohammed and a few ill-fitted advisers and yes-men. The leadership has turned the capacity and skills of high-ranking officials, including consular staff and journalists, into tools of oppression. The media has been fueling ultranationalist sentiment to justify its domestic and foreign policy failures. No public discourse exists on critical issues, including the war in Yemen, the Saudi-led boycott of Qatar, or the enduring challenges of unemployment and poverty — let alone discussion on the trial of Jamal’s killers or justice for political prisoners.

There was a point in time when hope for a societal transformation was centered on the return of thousands of Saudis who studied abroad. Instead, there has been a sharp rise in asylum seekers fleeing from Saudi Arabia. This figure more than doubled between 2015 and 2018. In European countries alone during the first half of 2019, the number of Saudi asylum seekers has shown a 106 percent year-on-year increase. The unabated persecution will, without a doubt, continue to fuel this trend as long as the current system is in place.

The Saudi monarchy might claim to be forward-thinking with its Vision 2030 modernization plan and efforts to court Western leaders. In reality, however, it has simply institutionalized a centuries-old monarchic legacy of violence, disenfranchisement and repression. Jamal’s brutal murder and the torture of female activists have brought this all to light.

In doing so, it has crystallized what Jamal and I have been warning, from different sides of the debate, for years: Unless power is decentralized away from the royal family and its cronies in power, Saudi Arabia’s drift toward more repression and destructive interventions abroad will continue unchallenged.

Written by Hala Al Dosari, a Robert E Wilhelm Fellow at the MIT Center for International Studies. The article was published by the Wall Street Journal on September 29, 2019.