MIT Security Studies Program director M Taylor Fravel co-authored an essay in Foreign Affairs on China’s “rapidly expanding and modernizing” of its nuclear armaments. This essay has been adapted from “The Dynamics of an Entangled Security Dilemma: China’s Changing Nuclear Posture,” published by the journal International Security in 2023. An excerpt is featured below.

Among the many issues surrounding China’s ongoing military modernization, perhaps none has been more dramatic than its nuclear weapons program. For decades, the Chinese government was content to maintain a comparatively small nuclear force. As recently as 2020, China’s arsenal was little changed from previous decades and amounted to some 220 weapons, around five to six percent of either the US or Russian stockpiles of deployed and reserve warheads.

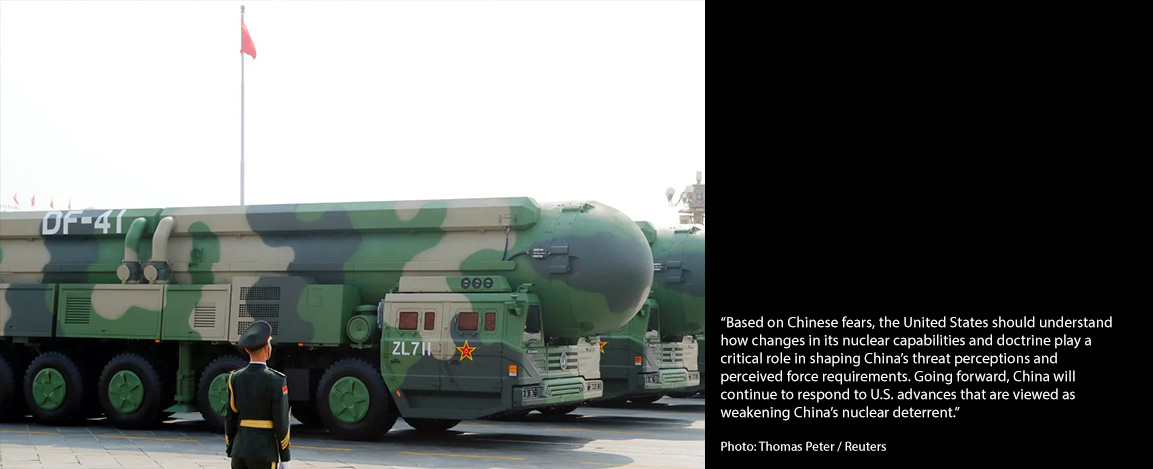

Since then, however, China has been rapidly expanding and modernizing its arsenal. In 2020, it began constructing three silo fields to house more than 300 intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). A year later, it successfully tested a hypersonic glide vehicle that traveled 21,600 miles, a test that likely demonstrated China’s ability to field weapons that can orbit the earth before striking targets, known as a “fractional orbital bombardment system.” Simultaneously, the Chinese government has accelerated its pursuit of a complete nuclear triad—encompassing land-, sea-, and air-launched nuclear weapons—including by developing new submarine- and air-launched ballistic missiles. By 2030, according to US Defense Department estimates, China will probably have more than 1,000 operational nuclear warheads—a more than fourfold increase from just a decade earlier.

China’s nuclear expansion is unlikely to be a focus of US President Joe Biden’s expected meeting with Chinese leader Xi Jinping at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit next week, but it is too important to be left entirely to defense strategists. Rather than maintaining only enough forces to be able to retaliate if attacked—China’s policy for decades—many in the United States now fear China’s nuclear buildout will give it offensive options as well. In 2021, Charles Richard, then the leader of US Strategic Command, described China’s nuclear expansion as a “strategic breakout” that will provide it “with the capability to execute any plausible nuclear employment strategy.”

To understand the rationale for this transformation, some in Washington have looked to the specific nature of the buildup. For example, Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall has suggested that, regardless of China’s intentions, the construction of hundreds of ICBM silos amounts to developing a first-strike capability: having enough weapons to destroy an adversary’s nuclear arsenal by attacking first. But seeking to infer motivations from capabilities alone can produce misleading worst-case assumptions, especially given the tendency to project US strategy onto potential adversaries, an analytical pitfall known as mirror-imaging.

Read the full article on Foreign Affairs.